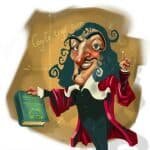

SIGMUND FREUD (May 6, 1856 – September 23, 1939)

Austrian neurologist, physiologist, psychologist, and influential thinker of the early 20th century. Founder of psychoanalysis.

Main accomplishments:

Coined the term “psychoanalysis.” Among his concepts and theories are Oedipus Complex; Levels of Consciousness, Libido; Id, Ego, and Superego; Defense Mechanisms; Psychosexual Stages of Development; Repression.

Best known published works include:

- 1895 – “Studies on Hysteria” with Josef Breuer

- 1900- “The Interpretation of Dreams”

- 1901 – “The Psychopathology of Everyday Life”

- 1914 – “On Narcissism”

- 1920 – “Beyond the Pleasure Principle”

- 1923 – “The Ego and the Id”

- 1929 – “Civilization and its Discontents”

Sigmund Freud was not only the father of psychoanalysis, but also a profound and wide-ranging writer and theorist whose ideas influenced virtually every aspect of modern life and culture. He developed or popularized almost all of the core notions that comprise what the average person thinks of as “psychology.” He’s responsible not only for the ideas of sexual repression and the sexual nature of neuroses, but for the professional approach to dream analysis, the concept of the ego (and id and super-ego), and most importantly, for talk therapy. Three-quarters of a century after his death, he continues to be the focus of heated argument and controversy, an object of both adulation and denigration.

EARLY LIFE

It is thanks to Freud that concepts such as “psychoanalysis,” “Freudian slip,” and the “unconscious mind” have shaped our perception of psychology and psychiatry—complete with talk therapy, a patient reclining on a couch, and dream analysis.

Freud was born in Moravia, in what is now the Czech Republic. His father, Jacob, 41 at the time, was 20 years older than his mother, Amalié, and despite facing poverty in Sigmund’s infancy, the two put all the money they could muster for Sigmund’s education when it became apparent how intelligent he was. They relocated to Vienna, Austria, where Freud graduated school with honors before joining the faculty at Vienna University. His early research involved eel physiology and the nervous systems of fish, and he soon opened his medical practice, specializing in neurology.

GROUNDBREAKING WORK

There was no separate industry for psychologists at the time; problems of the mind were problems of the brain. Freud’s patients did not necessarily have physical problems but were troubled by neuroses and other issues that we now consider principally psychological. He quickly abandoned the popular use of hypnosis and instructed his patients to talk simply about their problems. Much of the efficacy of Freud’s early treatments came from his sharp mind—he was able to see patterns of behavior that the patient might not, and to draw connections they had missed. “Talk therapy” was virtually unheard of before the end of the 19th century, so Freud was a pioneer in this field. Even staunch anti-Freudians who reject his theory of mind and sexual development, stand by the so-called “talking cure,” which, to this day, is the cornerstone of therapy and counseling.

At the same time, his views on human nature were, of course, subjective. He had a deep-set fear of death, and his analysis of his dreams led him to recognize a lifelong hostility towards his father, as well as early childhood sexual feelings for his mother. He often smoked, and used cocaine as a stimulant, recommending it as a remedy for many ills (including morphine dependency). His extreme and sometimes bizarre ideas spilled over into his marriage. In his 40s, he told his wife Martha that they would now live in celibacy because he needed to sublimate his libido in order to have more creative energy available to him. (There have always been rumors that Freud was having an affair with his sister-in-law; Carl Jung claimed to know about it but did so only after falling out with Freud).

EXPLORING THE UNCONSCIOUS MIND

Around the turn of the century, Freud published his first books advancing his theories of human psychology based on the 15 years he had spent treating patients. As developed by Freud, his technique of psychoanalysis involves leading the patient through free association, often using dreams as a starting point. The analyst remains as uninvolved as possible, interacting only as much as is necessary to keep the patient talking, or to pursue a conversational thread. Freud believed that unconscious memories—inaccessible to the conscious mind, but felt through dreams, yearnings, and instincts—were responsible for many neuroses and other mental ills. He didn’t invent the notion of the unconscious, but he popularized the idea of a layered mind, in which some thoughts or feelings occur “below the surface.” It’s a compelling notion, one the general public accepts so thoroughly that it’s hard to believe the idea didn’t exist 200 years ago.

Freud focused heavily on repression, the act of the mind burying feelings and memories it doesn’t want to deal with. Nothing can be removed from the mind, Freud said—it can only be moved to the unconscious, the mental basement, the unlit storage area. He later developed and systematized this idea further into the id, ego, and superego, taking their names from the Latin: the id is the source of such fundamental cravings as food, sex, and instant gratification; the superego is the conscience, formed by emulating the father-figure (or an idealized father figure); and the ego is the self that mediates between those two extremes and the practical needs imposed by the outside world. (The superego says stealing is wrong; the id says it’s hungry; the outside world has no food except for someone else’s loaf of bread. The ego struggles with what to do.) Problems between the id and superego are sometimes dealt with by defense mechanisms—the ego may intervene to rationalize a decision the superego disapproves of, may sublimate the id’s desires into other activities (as Freud believed his celibacy sublimated his sexual energies into success in his work), or may simply deny the reality of some unpleasant aspect of the outside world.

LATER YEARS

Many of Freud’s theories were too complex for the general public—and even the scientific community—to accept. He built his model of psychosexual development with references to ancient mythology in order to demonstrate that it was a universal model of the human condition, not one created by cultural factors. According to his “Oedipus complex,” the love or sexual feeling for one’s mother and hostility towards one’s father is a constant in human nature; most of human nature is similarly explained by sexual feelings, from the female’s jealousy of the male phallus to the male fear of castration. This is the component of Freudian thought most likely to be discarded by his followers and opponents.

Younger than Freud by 20 years, Carl Jung was one of his most promising students—the two corresponded from afar for years and had conversations that were known to last all day. In time, the two grew apart because of differences in their views of the unconscious. Jung believed Freud was too much of a pessimist, seeing only repression where Jung saw the unconscious’s ability to create and imagine. Though they were bitter enemies by the end of Freud’s career, Jung’s most famous notion—that of the collective unconscious—built directly on what he had learned from Freud.

In 1938, Freud—a nonobservant Jew—and his family left Austria after the Nazi annexation of the country. He died a year later. After dozens of operations on the mouth cancer caused by his cigar-smoking, he asked his doctor to end his life with a gradual overdose of morphine. He died on September 23, 1939, hopefully having conquered the fear of death that had plagued him for so long.

THE LEGACY

Although his contributions to the field of human psychology and psychiatry were substantial and undeniable—prompting Time Magazine to call him in 2001 “one of the most important thinkers of the last century—Freud’s theories and methods continue to stir controversy. A 2006 Newsweek article referred to him as “history’s most debunked doctor.”

The ongoing debate about the merits of Freud’s work is perhaps best summed up in W. H. Auden’s 1973 poem entitled “In Memory of Sigmund Freud:”

“if often he was wrong and, at times, absurd,

to us he is no more a person

now but a whole climate of opinion.”