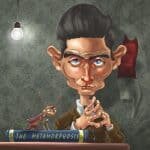

IMMANUEL KANT (April 22, 1724 – February 12, 1804)

German philosopher, anthropologist, and key thinker of the Enlightenment.

Main accomplishments:

- Produced over 50 philosophical volumes, including his masterpiece Critique Of Pure Reason (1781), as well as The False Subtlety Of The Four Syllogistic Figures (1762) and The Only Possible Argument In Support Of A Demonstration Of The Existence Of God (1763).

- Established a comprehensive branch of philosophy based on the “Copernican Revolution,” which connected the external world to the perception of those viewing it.

- Winner of the Berlin Academy Prize in 1754.

One of the most important and most challenging philosophers of all time, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) was the father of German Idealism and a lasting influence on philosophy and western thought to this day. Even though he had never left his hometown of Königsberg during his lifetime, his contributions to metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics had been, and remain to this day, significant.

EARLY LIFE

Baptized Emanuel Kant (he changed the spelling of his name later in life), Kant was born in 1724 in eastern Prussia (present-day Germany); his hometown, Königsberg, is now part of Russia. As a boy, he was an excellent student who received a strict religious education that emphasized the literal interpretation of the Bible and fluency in Biblical languages over liberal arts subjects like science and history. When his family recognized his scholarly aptitude, he was sent to school, eventually attending the University of Königsberg, where he was introduced to German and British philosophy, science, mathematics, as well as recent advances in physics introduced by Isaac Newton. After his father had suffered a stroke, Kant supported his family by working as a tutor, and continued to pursue his studies in his free time.

BURGEONING CAREER

In 1749, at the age of 25, Kant published his first work, Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces, a direct outgrowth of his university studies in which he defended a position of metaphysical dualism while arguing against the beliefs of many of his contemporary German philosophers. Other works followed, in both philosophy and science (a distinction not made as sharply in the 18th century as it is now). Interestingly, although Kant is now thought of as one of the more difficult and esoteric German philosophers whose work is full of complex concepts, one of his early contributions was the Nebular Hypothesis. In 1755’s Allgemeine Naturgeschichte, rarely translated into English because it is now of interest principally to historians of science, Kant refined Emanuel Swedenborg’s 1734 hypothesis that the solar system had begun as a cloud of gaseous material, which condensed into the “clumps” of the sun and planets. Kant concluded that for this cosmological model to work, those clouds—nebulae—must rotate, with gravity gradually crunching them down into the solid state of the solar system. This remains the most widely accepted cosmological model today, with modifications and tweaks made to incorporate expanding view of the universe. What’s fascinating is that Kant and Swedenborg were able to come to this conclusion hundreds of years before satellites, probes, and other tools of modern astronomy.

In that same year, Kant moved away from his tutoring job to become a more highly paid and respected university lecturer. Throughout his 30s, he wrote a variety of philosophical texts dealing with logic, emotion, and the existence of God. At the age of 45, he was made a full professor of logic and metaphysics, becoming caught up both in teaching and the response to his written work so far. Consequently, he didn’t publish again for 11 years. When he finally did, the result was Critique of Pure Reason, the most impressive work of philosophy by a single author—though perhaps because of its immense size, or possibly because Kant had been silent so long, it had little immediate impact.

The first of Kant’s “three critiques,” Pure Reason is difficult to sum up. He begins by rejecting the recent conclusions of his friend and fellow philosopher David Hume, whose work argued that ideas all begin as representations of sensory (i.e., physical) experience. Kant claimed that we could have knowledge not based on empirical experience—indeed, that much important and applicable knowledge had begun as such—and spent 800 pages proving his argument. The book is dense, filled with thought experiments and specialized language that doesn’t translate well into English.

The work rejuvenated Kant’s interest in publishing, or maybe just gave impetus to his writing. The 1780s were a busy time for him, with the publication of his first works on moral philosophy as well as his second and third critiques (Critique of Practical Reason and Critique of Judgment). Naturally, he attracted a good deal of criticism, but his influence was undeniable, and the school of German Idealism formed with his pupils and younger colleagues. A true workaholic, he never married. He did, however, have a big following; when he died shortly before his 80th birthday, regularly publishing until the last year of his life, he was mourned by many.