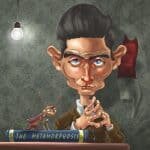

ERNEST HEMINGWAY (July 21st, 1899 – July 2nd, 1961)

American journalist and author. Helped to chronicle the “Lost Generation” of American expatriates in Europe.

Main accomplishments:

- Author of 10 novels—including The Sun Also Rises (1925), A Farewell To Arms (1929), and The Old Man And The Sea (1952)—10 short story collections, and five non-fiction collections, including The Sun Also Rises (1925), A Farewell To Arms (1929), and The Old Man And The Sea (1952).

- Winner of the Bronze Star and the Silver Medal of Military Valor for military service during WWII; winner of the 1953 Pulitzer Prize for The Old Man And The Sea, the 1954 Nobel Prize for Literature, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award of Merit in 1954; rated the Top Reporter of the 20th Century by the Kansas City Star in 1999.

- Avid hunter and outdoorsman; embarked on two safaris to Africa, the latter of which saw him surviving two successive plane crashes.

As famous for his colorful and adventurous life as for his acclaimed novels, Pulitzer and Nobel-winning writer Ernest Hemingway fit a prodigious amount of living into his 62 years. Ambulance driver, big-game hunter, war reporter, record-breaking fisherman—it was sometimes hard to separate the man from his characters. His simple, clear, and distinctive style revolutionized literature, and his work continues to be taught in nearly every high school, college, and university.

EARLY LIFE

The son of a doctor, Hemingway grew up in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park. His domineering singing instructor mother sometimes dressed young Ernest in girl’s clothes to match his older sister—she had wanted twins, and he had failed to be a pair. Ernest rejected his mother’s plans for him to pursue a career in music and instead took to athletics. He became an outdoorsman at an early age, camping and hunting in the wilderness around his family’s summer home on Walloon Lake in Michigan. He boxed in high school, but also discovered a love of literature and the sports writing of columnist Ring Lardner.

Inspired by Lardner’s storytelling abilities, Hemingway decided not to go to college, a career as a journalist instead. He briefly worked for the Kansas City Star before joining, in 1918, the Red Cross Ambulance Corps on the Italian front. The stint was cut short by an injury. But even though he was hit by a mortar shell, Hemingway—only 18 at the time—dragged a wounded soldier to the ambulance. He spent the rest of his time working in a hospital, reading, and drinking. However, his experiences on the front inspired his novel, A Farewell To Arms.

After leaving Europe at war’s end, Hemingway seemed to have trouble staying still, moving back and forth between Chicago and Toronto in the space of a year. He worked for several newspapers, married his first wife, Hadley Richardson, and met writer Sherwood Anderson, who had just published his best-known work Winesburg, Ohio. Hemingway’s friendship with Anderson would last for six years until Hemingway mocked Anderson’s best-selling novel, Dark Laughter, a book strongly influenced by James Joyce’s Ulysses.

THE LOST GENERATION

Before his fallout with Hemingway, Anderson was instrumental in the formation of the group that became known as the Lost Generation—a term coined by an American writer Gertrude Stein in the 1920s to describe the generation that grew up during WWI and had become disillusioned and cynical. Anderson suggested Hemingway spend some time in post-war Europe; following this advice, Ernest went to Paris with his wife. There, he worked as a war correspondent for the Toronto Star, covering the events of the Turkish War of Independence. Anderson introduced Hemingway to the expatriate community by writing a letter of introduction to Gertrude Stein, who had moved to Paris in 1903 and ran literary salons. These gatherings had attracted the likes of Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, John Dos Passos, and F. Scott Fitzgerald., among other writers, artists, and intellectuals. Members of this close-knit circle formed passionate friendships but also had plenty of arguments, fuelled by jealousy and alcohol.

Hemingway was one of the last writers of the Lost Generation to publish his fiction. His short story collection, In Our Time, was released in Europe in 1924 after fellow expatriate Fitzgerald’s two bestselling novels had turned him into an international celebrity. While Fitzgerald’s work—especially his first, This Side of Paradise, written before his encounters with the expatriates—could be ornate and decorative, Hemingway’s was stripped down. On Stein’s advice, he eliminated any unnecessary words, especially adjectives. His short sentences could even seem choppy and blunt; he initially worried that the literary community would not look beyond this no-frills style to see his merit. (Hemingway’s simple language prompted his literary rival, William Faulkner, to quip: “He has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary.”

However, Hemingway’s prose was well received from the start. While the critics loved him, some of his friends were turned off by his rough, boisterous, and brawling ways. Besides alienating his early mentor Anderson, Hemingway also fought with Fitzgerald, accusing him of not being “artistic enough” and writing short stories that were shoddy and sensational.

Still, despite the quibbles, Hemingway drew inspiration from his Lost Generation companions—it was Fitzgerald’s 1925 book, The Great Gatsby (which Hemingway read while it was being written) that convinced Hemingway to pen his own novel; The Sun Also Rises was published the following year.

INTERNATIONAL CAREER

In the wake of Hemingway’s divorce and remarriage, another collection of short stories followed—and his second novel, A Farewell to Arms, came on the heels of his father’s suicide. The book, published in 1929, was a significant commercial success.

The Lost Generation community fell apart amid arguments and accusations—homosexuality was one often leveled against Hemingway, who was vocally critical of homosexuals—and it was also suggested that he had let his success go to his head. In 1931, just as Hemingway’s reputation as one of the greatest writers of his generation started to take hold, he moved to Key West, Florida. He continued to be creative throughout the 1930s, publishing two books based on his own intrepid travel experiences—a bullfighting “bible,” Death in the Afternoon (1932), and an account of his African safari in Green Hills of Africa (1935); he also published two short stories, “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” (1936) and “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” (1936).

In 1937, Hemingway went to Spain—and back to his journalism roots—to report on the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance. His experiences inspired the critically acclaimed 1940 novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls. The same year, the newly divorced (for the second time) author married journalist Martha Gellhorn, with whom he had worked while covering the war in Spain. The couple settled in Finca Vigia, the Cuban estate where Hemingway lived, off and on, (and wrote The Old Man And The Sea) until 1960.

During WWII, Hemingway served as a sub hunter and war correspondent. He divorced Gellhorn and married his fourth wife, Mary Walsh. He resumed his writing with the 1950 novel, Across The River and Through the Trees, which was met with the worst reviews of his career. However, The Old Man and the Sea followed in 1952, earning him, the following year, the Pulitzer Prize. A year after that, he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. “for his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style.” He was unable to accept the Prize in person due to severe injuries—not long after surviving a plane crash so catastrophic that several newspapers published his obituary, he was severely burned in a brushfire, which kept him confined while he recovered.

LATER YEARS AND DEPRESSION

Thirty years after the peak of the expatriate community in Europe, Hemingway wrote A Moveable Feast, his memoir of the era, though it wasn’t published until after his death. After an initial failed attempt, he committed suicide in 1961, a few weeks before his 62nd birthday. He had been receiving electroshock treatments as a remedy for his depression, but blamed the treatments for ruining his memory. Depression probably ran in his family—several relatives had committed suicide, and 35 years after his death, his granddaughter Margaux, took her life with an overdose of pills.

He had continued to work in the last years of his life, and a number of his books were published posthumously. One of these, Islands in the Stream, was written in response to the criticism against Across The River and Through the Trees; though unfinished, a substantial portion of it was written, and his famous novella, The Old Man And The Sea, was intended to be its fourth and final part.

Hemingway left behind a legacy of minimalist, existential writing, as well as a lifetime of travel and exploration around the world. In 1950, the New York Times called him “the most important author living today, the outstanding author since the death of Shakespeare.”